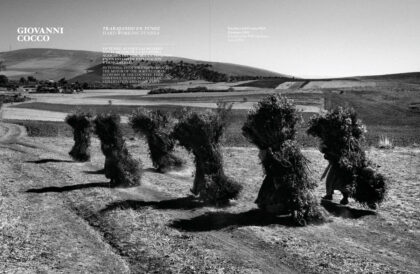

Toiling Tunisia

2013

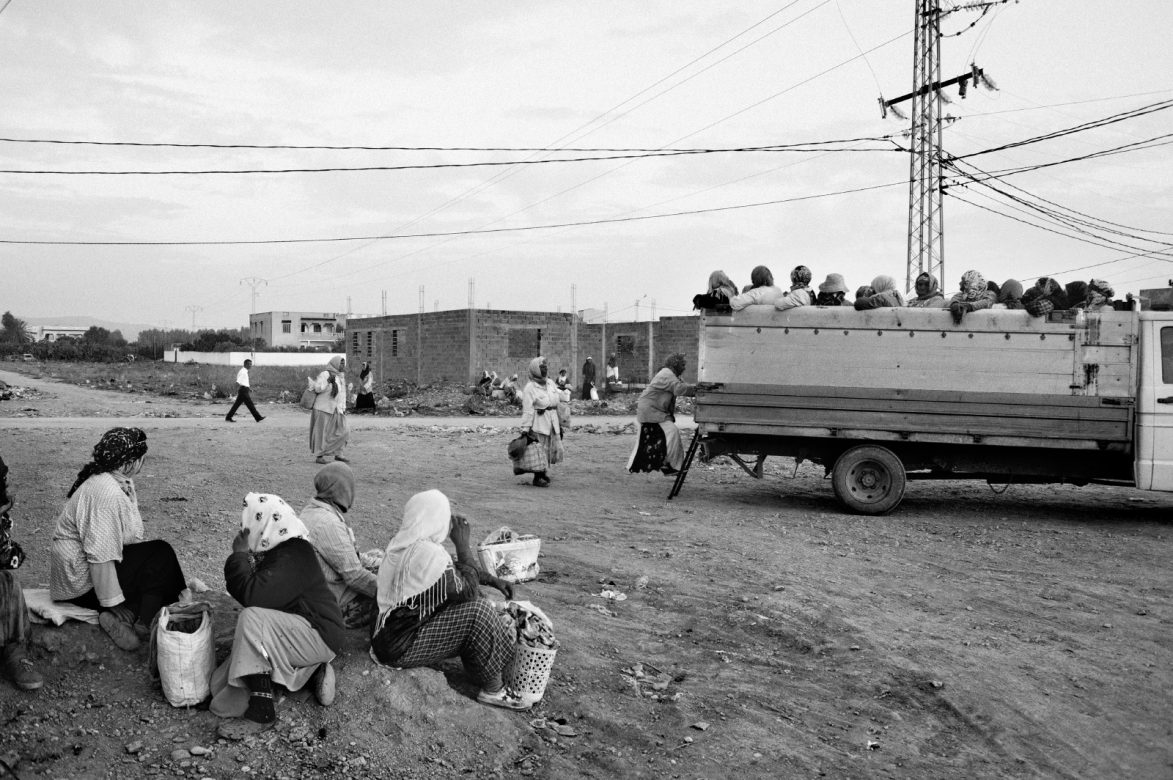

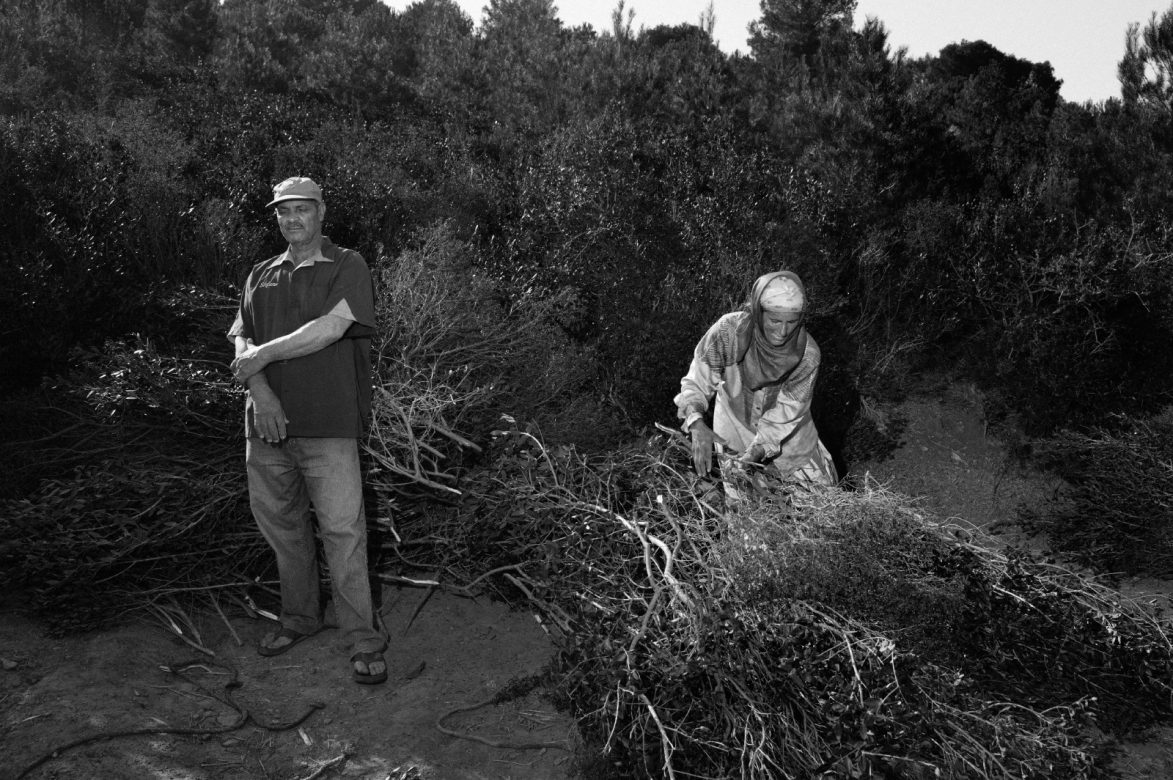

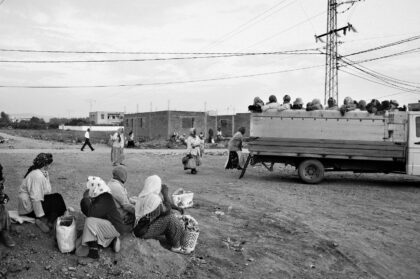

Every dawn in rural Tunisia, thousands of women are enlisted by day labourer recruiters and taken to the fields. No man bends down to work the land. Agricultural work is women-only work. The fruits of their labour not only supply the rural distribution chain to which they belong, but also the whole of Tunisia and beyond. They are the silent motor of the country’s agricultural economy. The landowners’ clients come from the capital and the south but also from neighbouring countries and from Europe. These rural women make up more than 35 per cent of the female population and represent between 70-80 per cent of the agricultural workforce. Although almost all agricultural work is the result of their labour, the wealth they derive from it is very small: an average eight-hour day corresponds to a wage that fluctuates between three and fours euros a day.

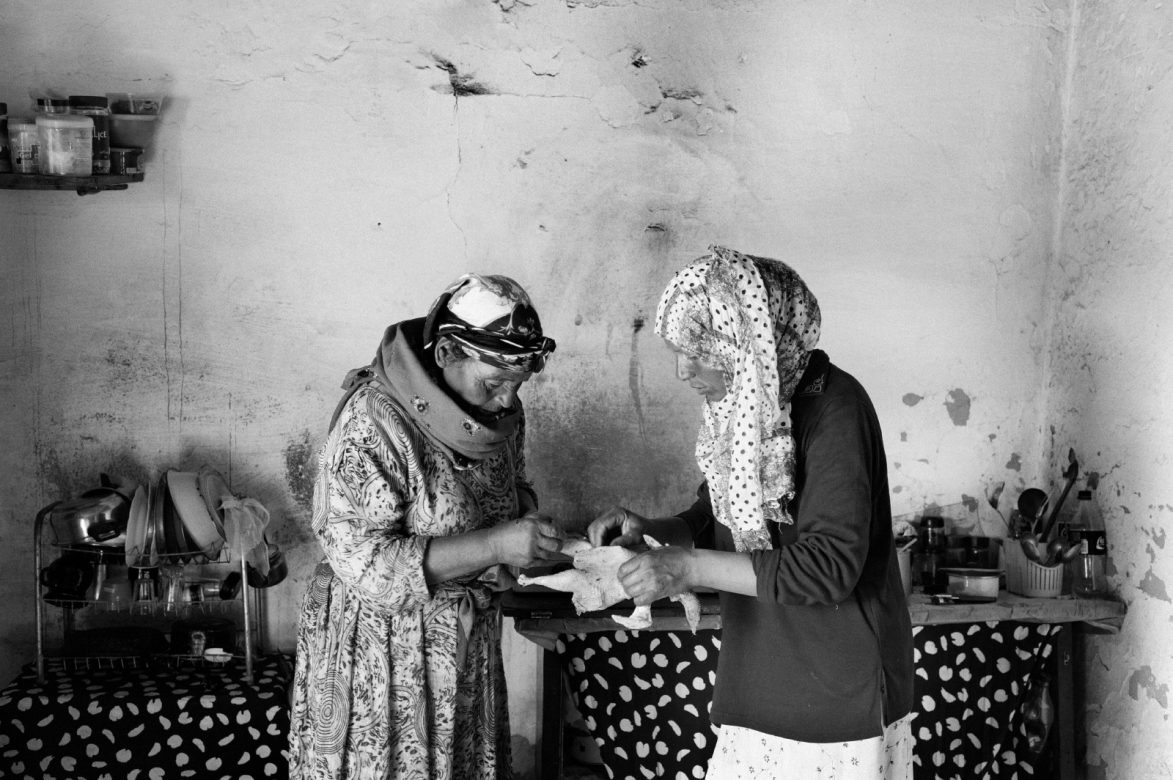

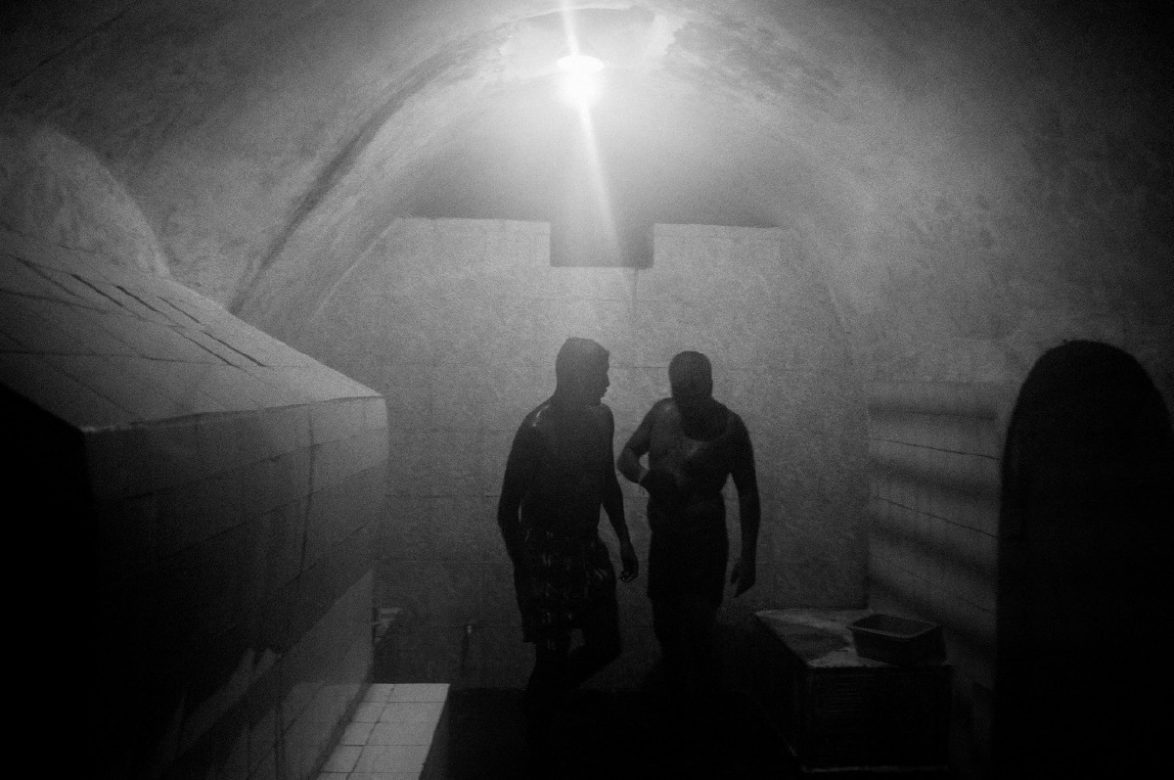

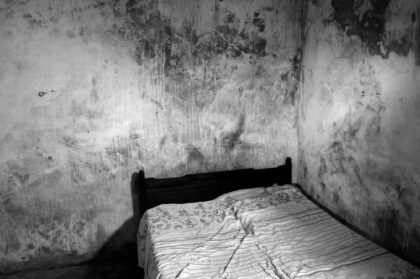

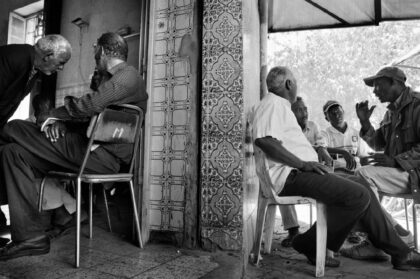

In Tunis I met the associations and feminist rumors most prominent during the post- revolution period: female bloggers, militant activists, femen. But there was an unseen side of Tunisia that awaited me. A slow-paced, disillusioned world full of contradictions. A world comprised of young mothers and grandmothers, and adolescent girls yet to marry. They had much in common – they had left education early, for example – and the majority were illiterate.

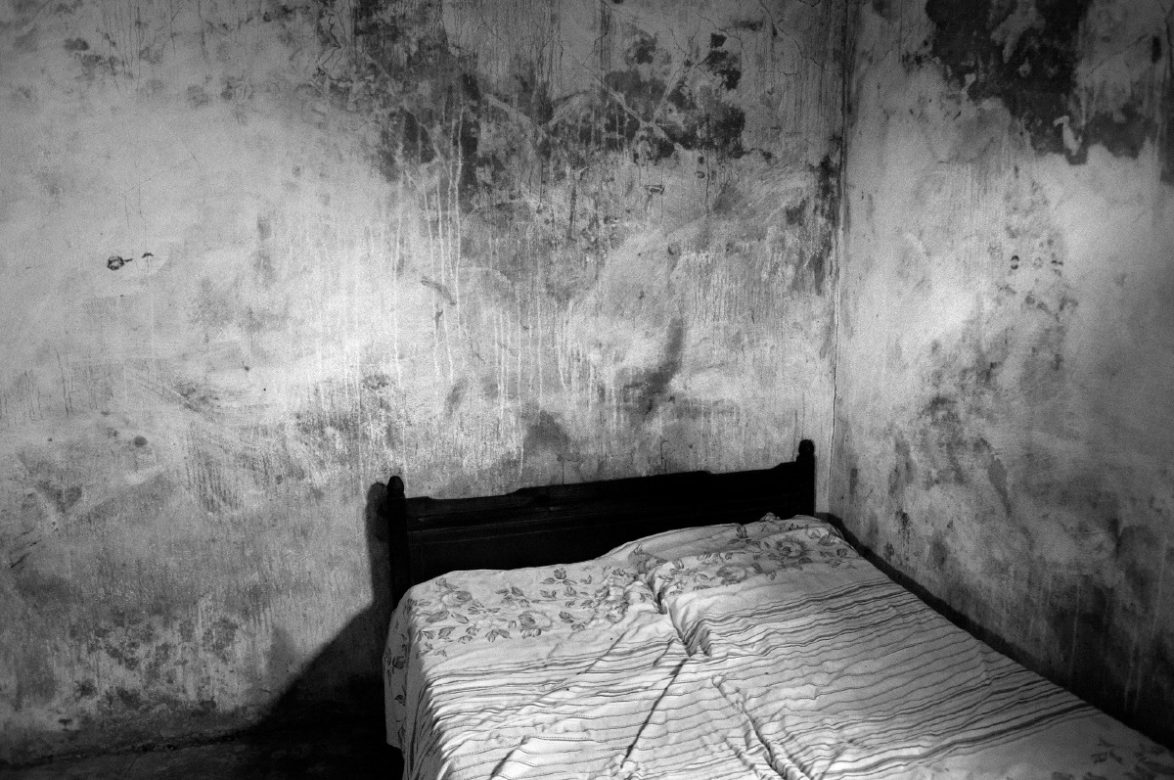

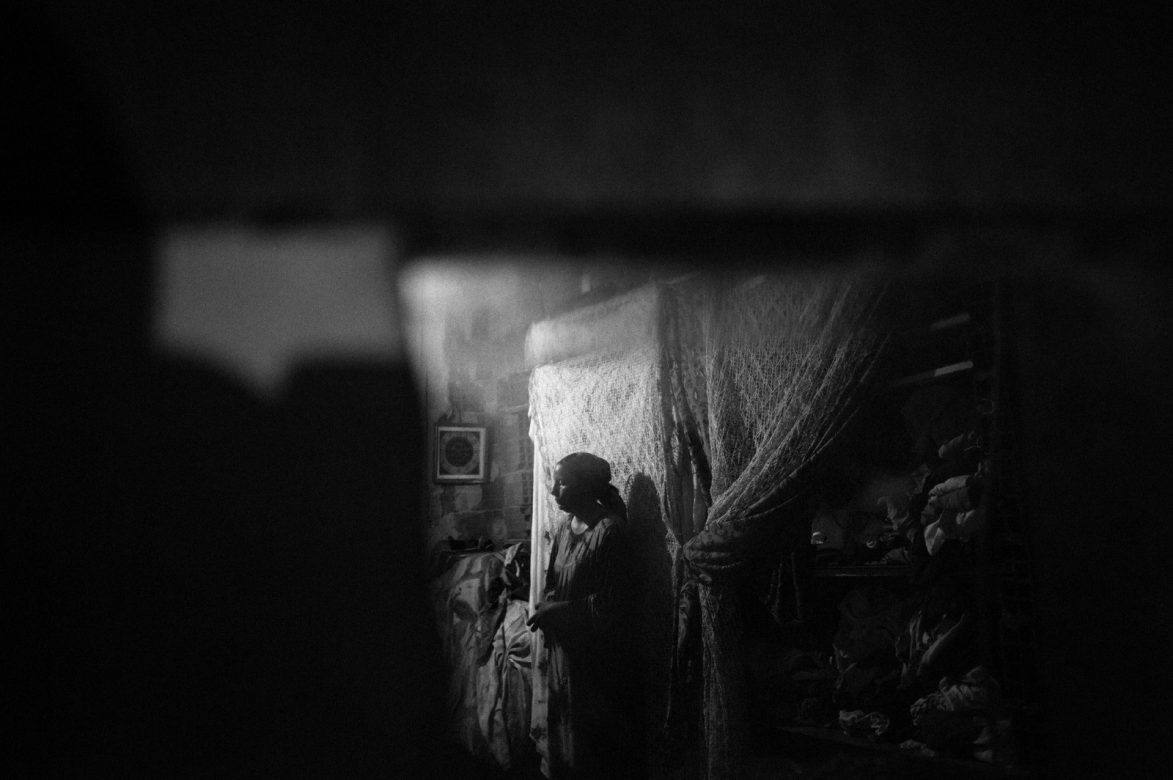

This is the world of the women farmers. I have met many of these women as Dorsaf in the outskirts of the small town of Jendouba. She is 16 years old and has already been working in the fields for four years. She learnt the trade from her grandmother and cannot imagine doing anything else. Hadda, who can’t remember how old she is. Her pace of life has not changed since the day she was born: she grew up between housework at home and hard work in the fields.

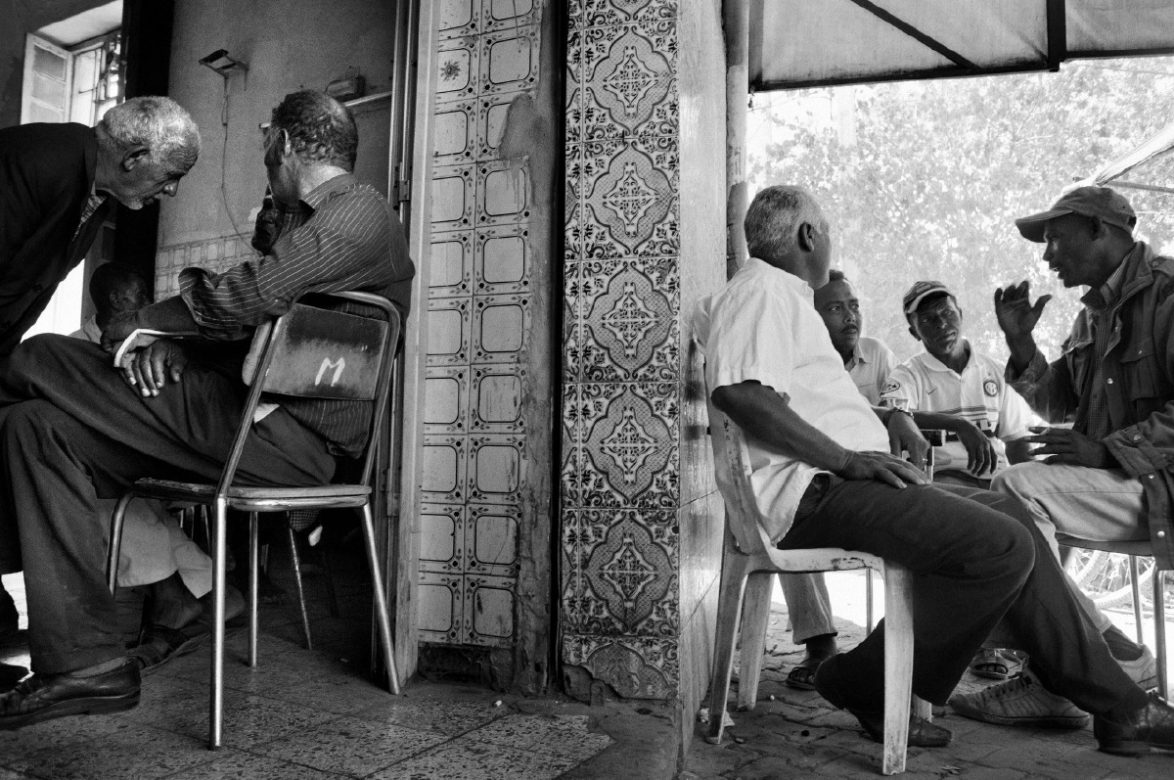

The relationship with men, husbands and landowners, force them into conditions of subordination and exploitation and relationships of dominance, inequality and submission. These women’s crucial role in contributing to the global economy and the reduction of poverty levels in their communities. Their work often compensates for their husbands’ unemployment and constitutes the only source of family income.

Today Tunisia finds itself a few steps away from the approval of a new constitution, following the elections in October 2011 of the Constituent Assembly. Articles 20 and 45, which for the first time in an Arab country sanction equality of citizens before the law without discrimination and with equal opportunity, have been approved. Article 45 states that the Tunisian state will oversee the elimination of causes of violence against women.

It is a fundamental and unique step in a Muslim country. Whilst in the capital the approval of the Constitution’s articles is celebrated, a profound analysis of the country’s cultural dynamics – which make gender equality and equal opportunities unattainable realities – is, however, necessary. My aim is to interrogate the relationship between rural world and gender bias in order to promote the cultural understanding of the institutional subordination of rural women in Tunisia.