The landing dock for boats that transported people and goods to the island of Goli Otok. Croatia, Goli Otok, 2016.

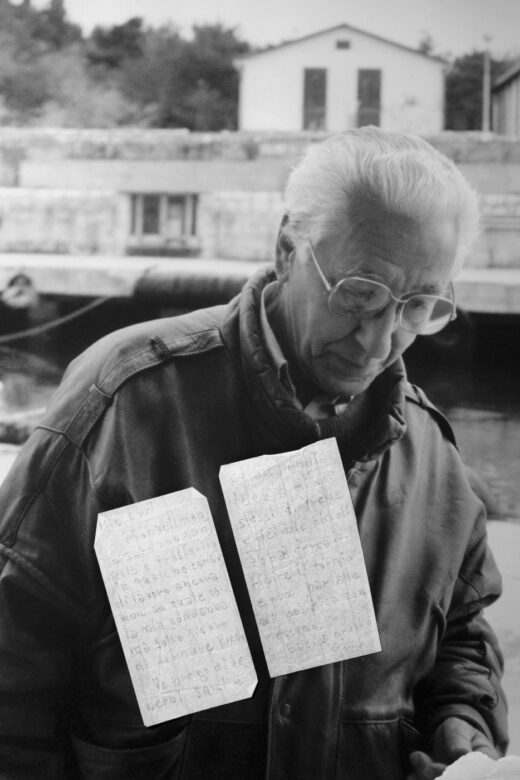

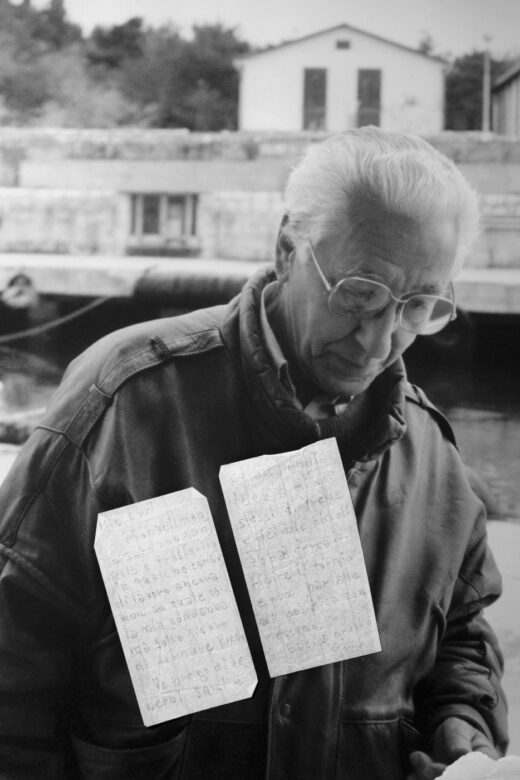

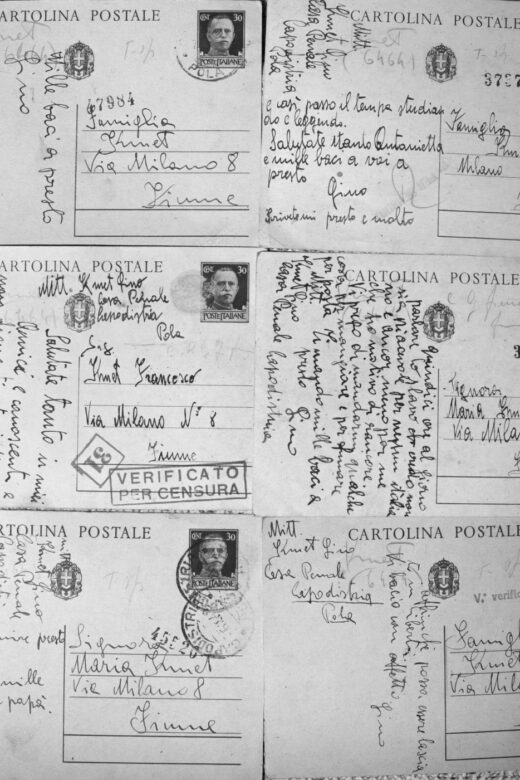

“Don’t speak about politics with anyone,” wrote Gino Kmet to his father, using cigarette papers as writing paper. Pictured in a photograph from ‘93, taken on the island of Goli Otok, Gino was a resistance fighter and was deported from ‘49 to ‘51. Fiume, 2016.

The only trees present on the island today were planted by prisoners between ‘49 and ‘56 during their so-called “voluntary work”. After planting the trees, prisoners had stay on their feet for long periods of time. They were forced to protect the plants from the sun and the wind with their own bodies. Goli Otok, 2016.

May Day celebrations on the island of Goli Otok (the photo probably dates back to 1954). It was stolen by a prisoner from the Goli Otok police archives, and for many years it was the only evidence of the existence of a concentration camp on the island.

An ex-cinema for detainees. The concentration camp on Goli Otok was officially closed in ’56, although the last deportees did not leave the island until ’59. Subsequently the concentration camp became a detention centre for common criminals until ’88. Goli Otok, 2016.

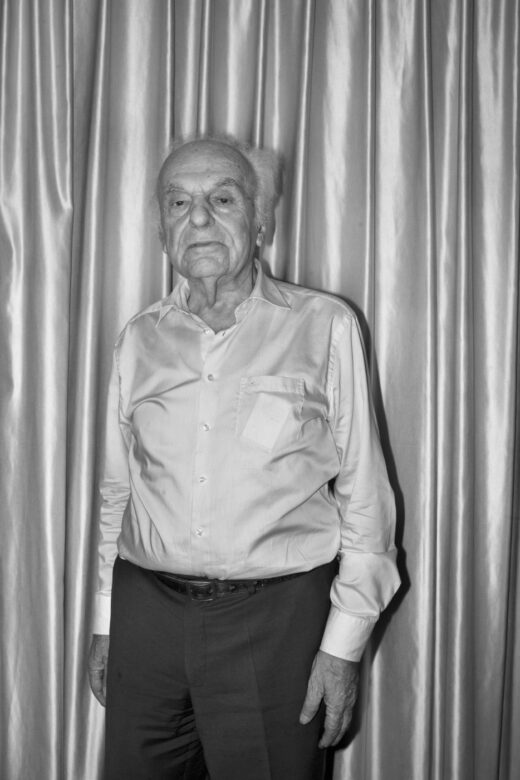

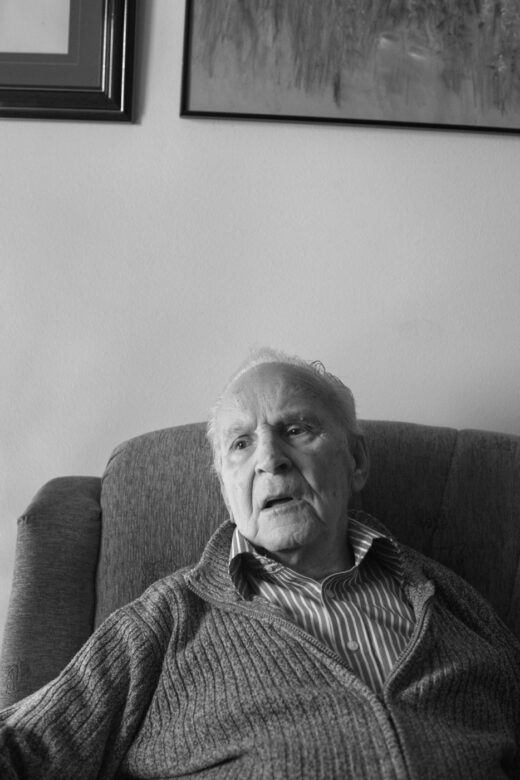

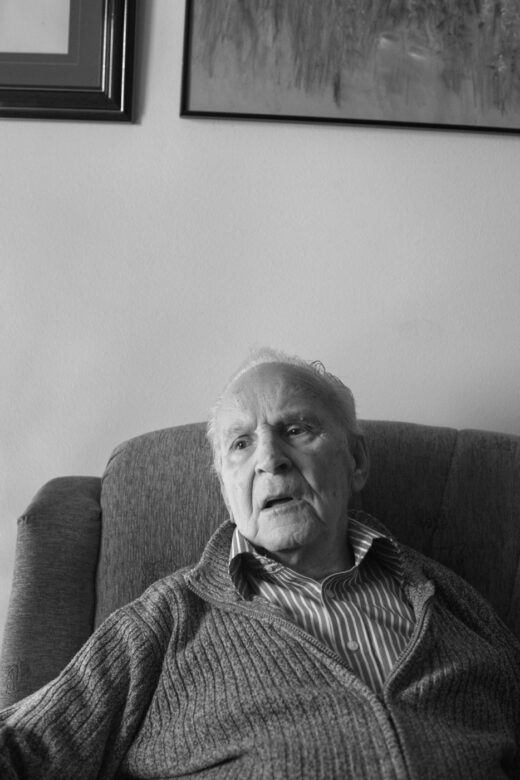

Giacomo Scotti, journalist and historian, pictured in his house in Fiume. With his book, Goli Otok Ritorno all’Isola Calva, he was the first person to officially talk about the existence of the prison camp in 91'. Fiume, 2016.

Before the creation of a “correctional camp” on the island, there was nothing. Everything was constructed, using this stone, by the deportees themselves. The Gulag was concealed from public opinion through the cover-up of a state complex employed to extract marble. Goli Otok, 2016.

A photograph of Gino Kmet in the hands of his daughter, Irene Mestrovich Kmet. Gino was a resistance fighter and was deported to the island from ‘49 to ‘51. Fiume, 2016.

Goli Otok is an island in the northern Adriatic Sea, close to the Croatian coast. Goli Otok, 2016.

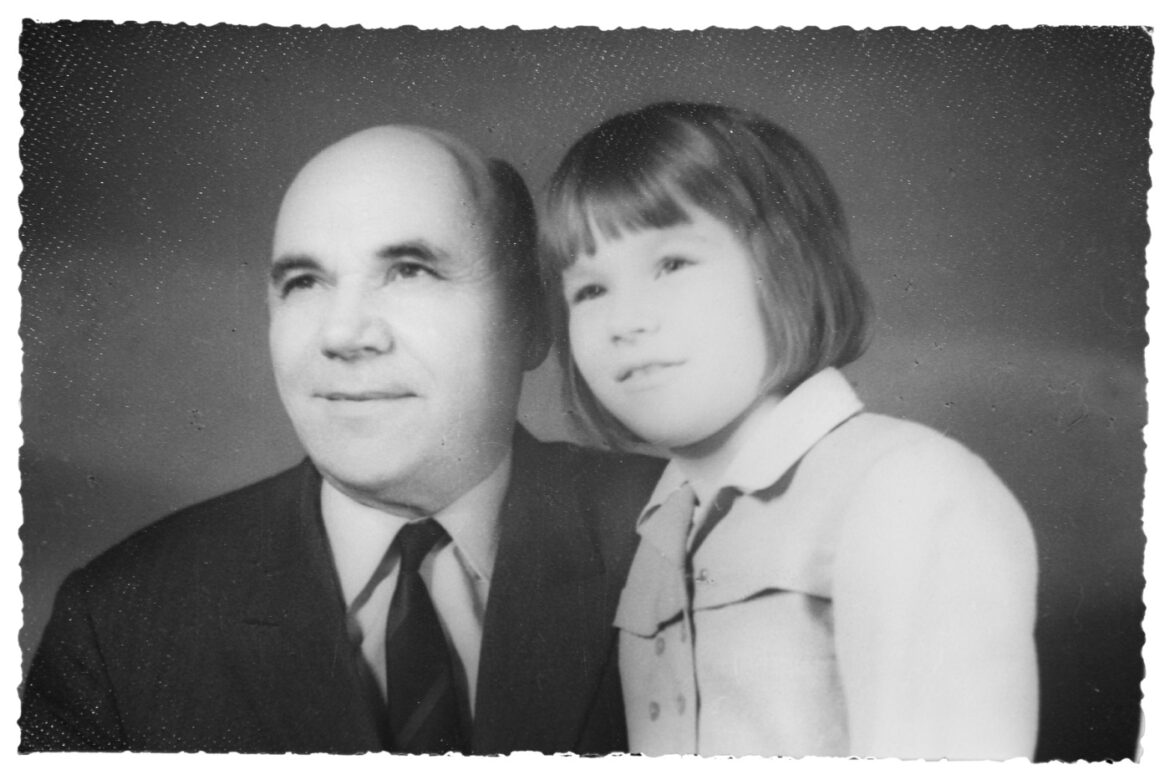

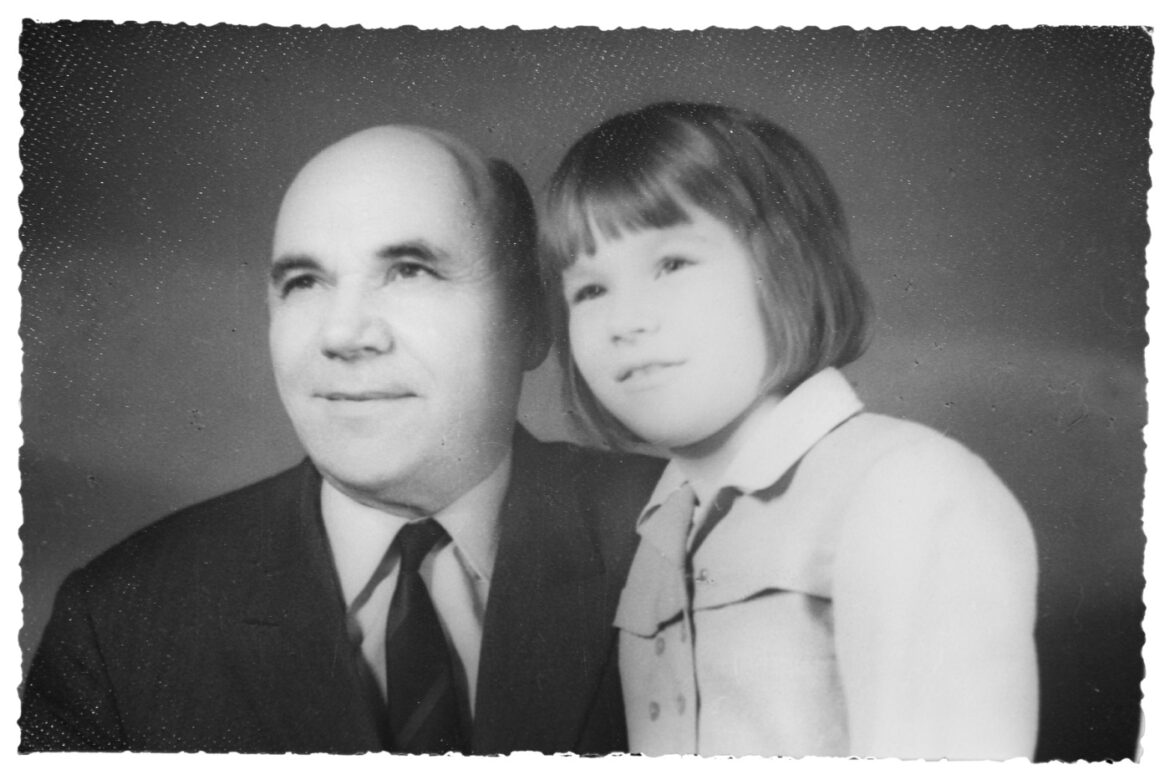

A photo of Džemal Dautcehajić (1910–1995) with his daughter, Jasmina Bavoljak. Džemal was deported to the island of Goli Otok from ‘50 to ‘52. Following the opening of the confidential archives of UDBA, the secret police of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Jasmina discovered that she had been spied on for years as the daughter of a deportee. Zagreb, 2016.

The concentration camp on the island of Goli Otok was officially closed in ’56, although the last deportees did not leave the island until ’59. Subsequently the concentration camp became a detention centre for common criminals until ’88. Goli Otok, 2016.

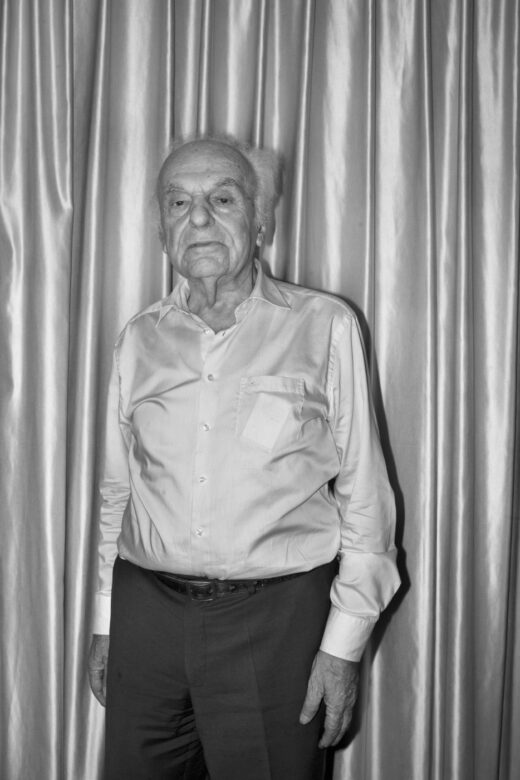

“The aim of this place was to destroy human dignity.” Paule Ravlić, detained on the island of Goli Otok from 11 September ’49 until 17 October ’52. He is one of the few survivors still alive. Zagreb, 2016.

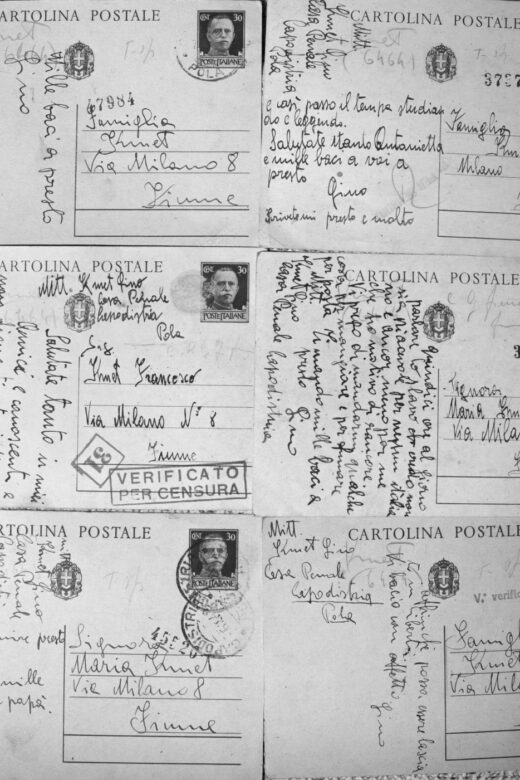

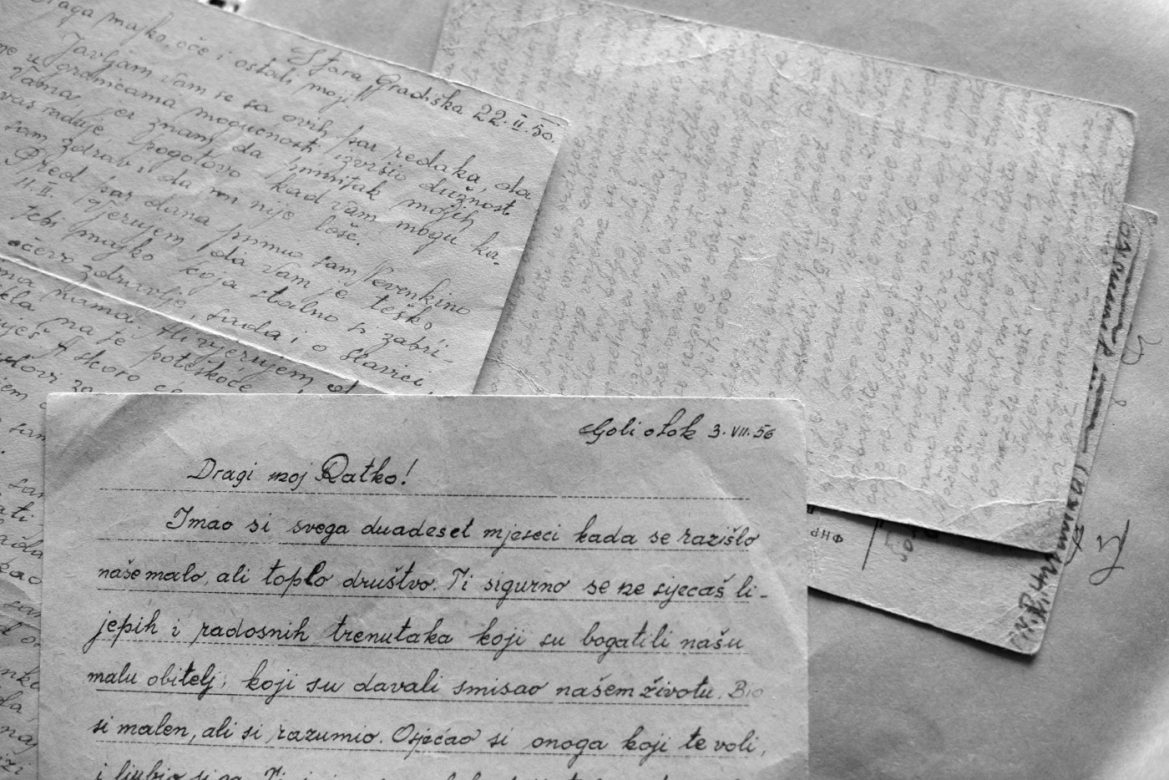

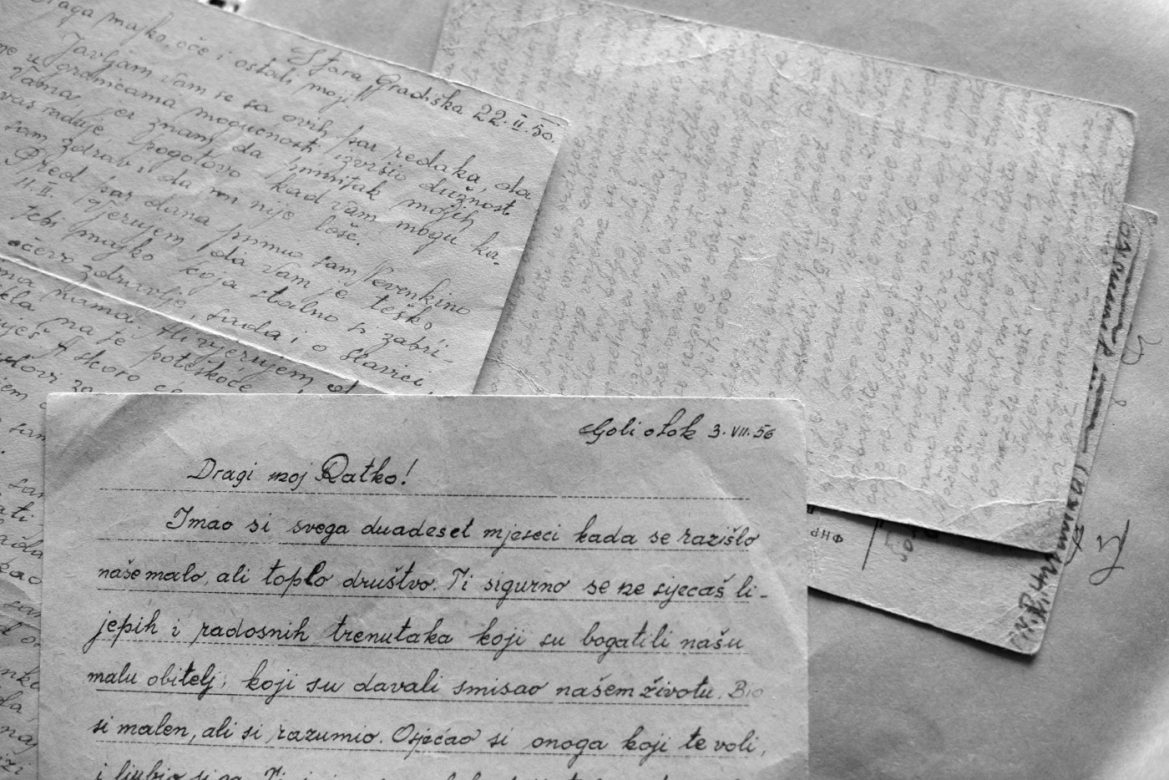

Postcards that Gino Kmet sent to his family during his imprisonment. Fiume, 2016.

“When he returned home, my father didn’t want to tell me the truth about Goli Otok.” Irene Mestrovich Kmet, daughter of Gino Kmet, a resistance fighter deported to island from ’49 to ’51. Fiume, 2016.

An ex-concentration camp for men. Goli Otok, 2016.

Naked Island—as it was called by the Slavs due to its barren, rocky appearance—is a large chalky rock, 200 metres high and with an area of 5km², that is pounded by the freezing Bora in winter and scorched by the sun in summer, which is why it is arid and almost devoid of vegetation. Goli Otok, 2016.

“I’ll go to Bucharest to hear what Stalin says.” It was probably due to this phrase, said in a bar to other people, that Petar Radošević was deported to island of Goli Otok from ’54 until ’56—explains his son, Ratko Radošević, depicted in the photograph. Medulin, 2016.

One of the remaining original structures of the Goli Otok concentration camp. Goli Otok, 2016.

“I’ll never forget the cruelty of other prisoners, who were forced to beat me during the Kroz Stroj—the corridor of welcome—on my arrival to island.” Zlatko Hill, 91, one of the few witnesses still alive. He was 20 when they arrested him: they took him to Sarajevo and then to Goli Otok for 47 months, until ’53. He is one of the few survivors still alive. Zagreb, 2016.

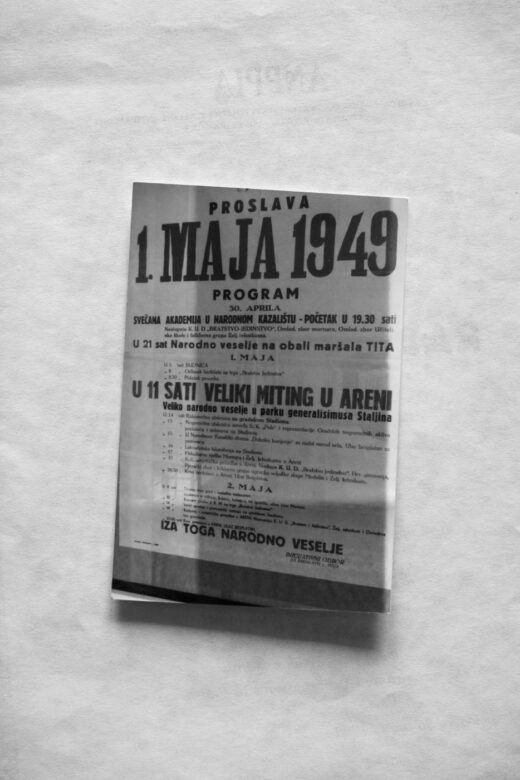

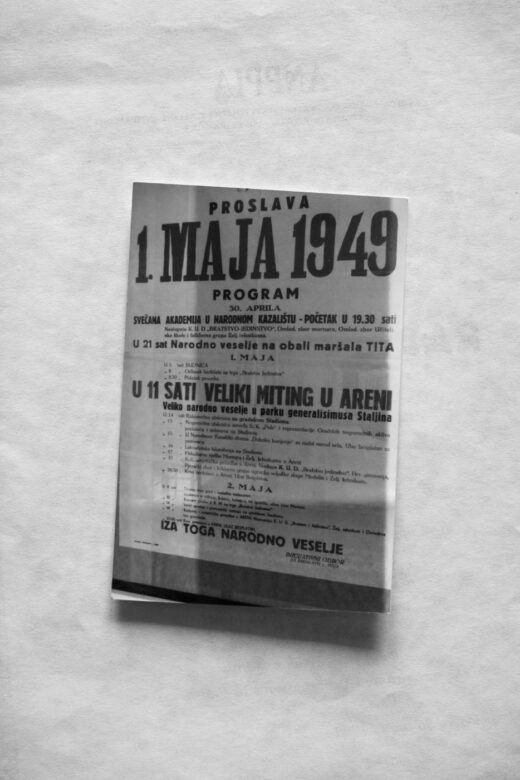

This poster promotes two large events for the celebrations on May Day 1949. But in ‘49 Stalin and Tito had already separated, so it made no sense to hold a celebration in the large park named after Stalin. Those that attended, heading to the park named after Stalin, were probably considered supporters of Stalin, which was cause for persecution. Medulin, 2016.

Rocks of calcium carbonate. Before the creation of a “correctional camp” on the island, there was nothing. Everything was constructed, using this stone, by the deportees themselves. The Gulag was concealed from public opinion through the cover-up of a state complex employed to extract marble. Goli Otok, 2016.

Giacomo Scotti, journalist and historian, pictured in his house in Fiume. With his book, Goli Otok Ritorno all’Isola Calva, he was the first person to officially talk about the existence of the prison camp. Fiume, 2016.

Ex-offices. The concentration camp had three industrial centres: unit one, for the production of stone (tiles and concrete masonry blocks); unit two, for the production of wood (furniture); unit three, for the production of metals (frames for agricultural machinery, pipes, parts for naval engineering). Goli Otok, 2016.

An ex-administrative centre. Here the deportees were registered and their correspondence was rigidly censured. Goli Otok, 2016.

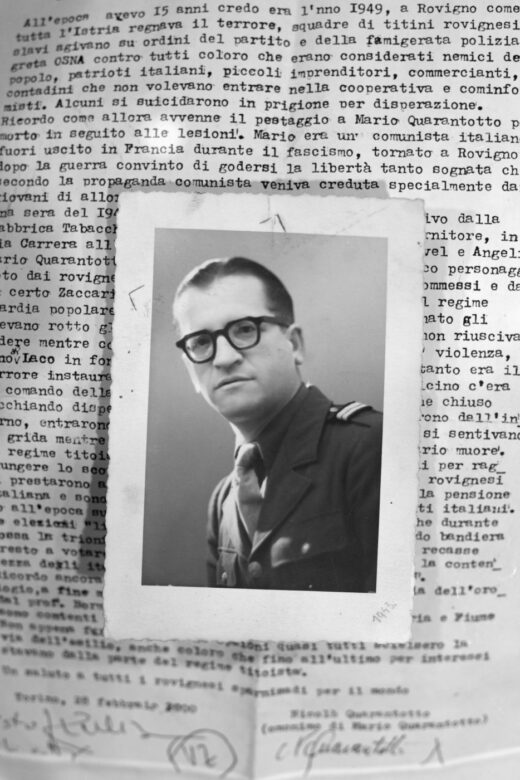

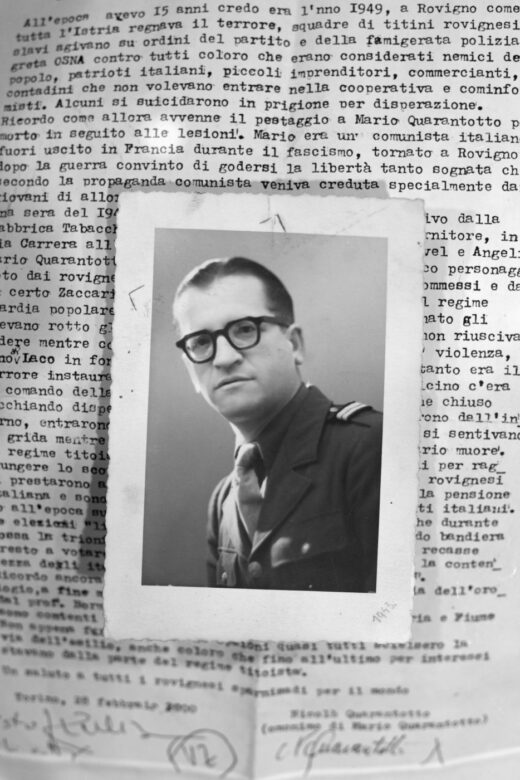

Mario Quarantotto was not even 20 when he was picked up on the streets of Rovigno (1950). He was beaten up before arriving on the island, where he died shortly afterwards. The cause of death reported to his family: sunstroke. The body was never found. There was no cemetery on the island. His body was probably thrown into the sea or cremated. Rovigno, 2016.

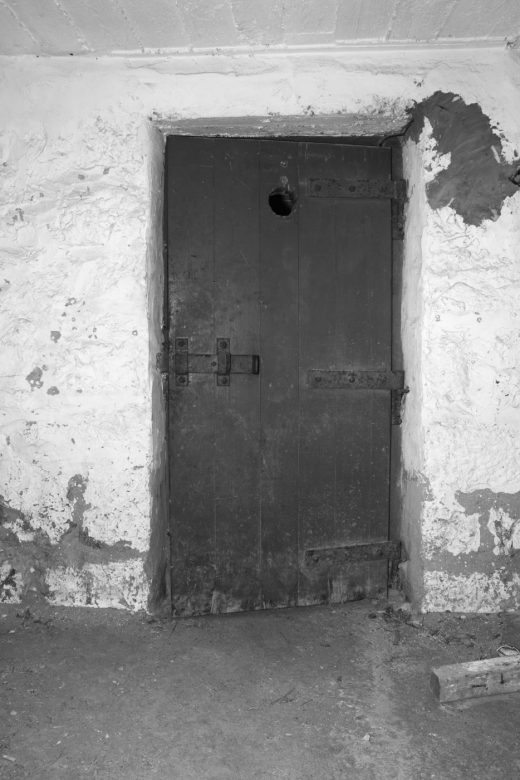

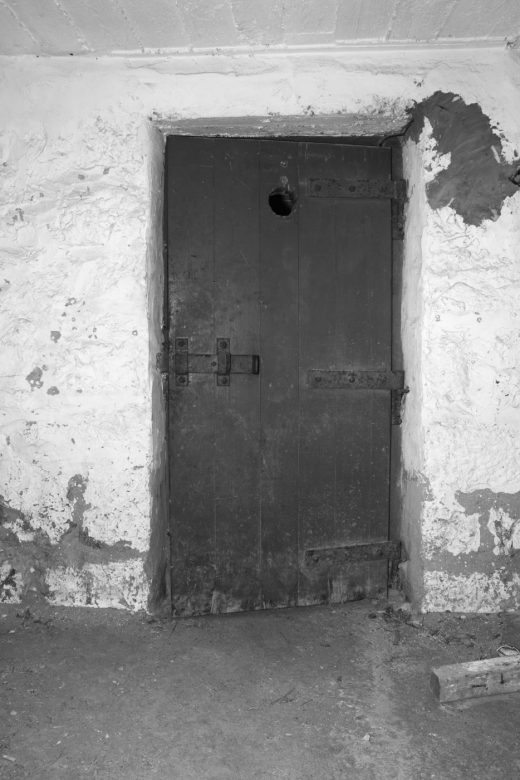

One of the solitary confinement cells in the prison complex. Goli Otok, 2016.

Jasmina Bavoljak, daughter of Džemal Dautcehajić, deported on the island of Goli Otok from ’50 to ’52. Following the opening of the secret archives on UDBA—the secret police of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia—Jasmina discovered that, as the daughter of a deportee, she had been spied on for years. Zagreb, 2016.

The courtyard of the first building constructed on the island, named Kamena (literally “of stone”) by the prisoners. Goli Otok, 2016.

“My dear Ratko!” So began the letters that Petar Radošević—deported on the island of Goli Otok from ’54 to ’56—wrote to his nine-year-old son, Ratko Radošević. The letters were subjected to checks and censors. Nobody could recount what was actually happening on the island. Medulin, 2016.

Ex-offices. The concentration camp had three industrial centres: unit one, for the production of stone (tiles and concrete masonry blocks); unit two, for the production of wood (furniture); unit three, for the production of metals (frames for agricultural machinery, pipes, parts for naval engineering). Goli Otok, 2016.

Darko Bavoljak—president of Ante Zemljar, based is Zagreb—visits the island. The association, made up of victims’ relatives, focuses on conserving and divulging the story of Goli Otok. Goli Otok, 2016.